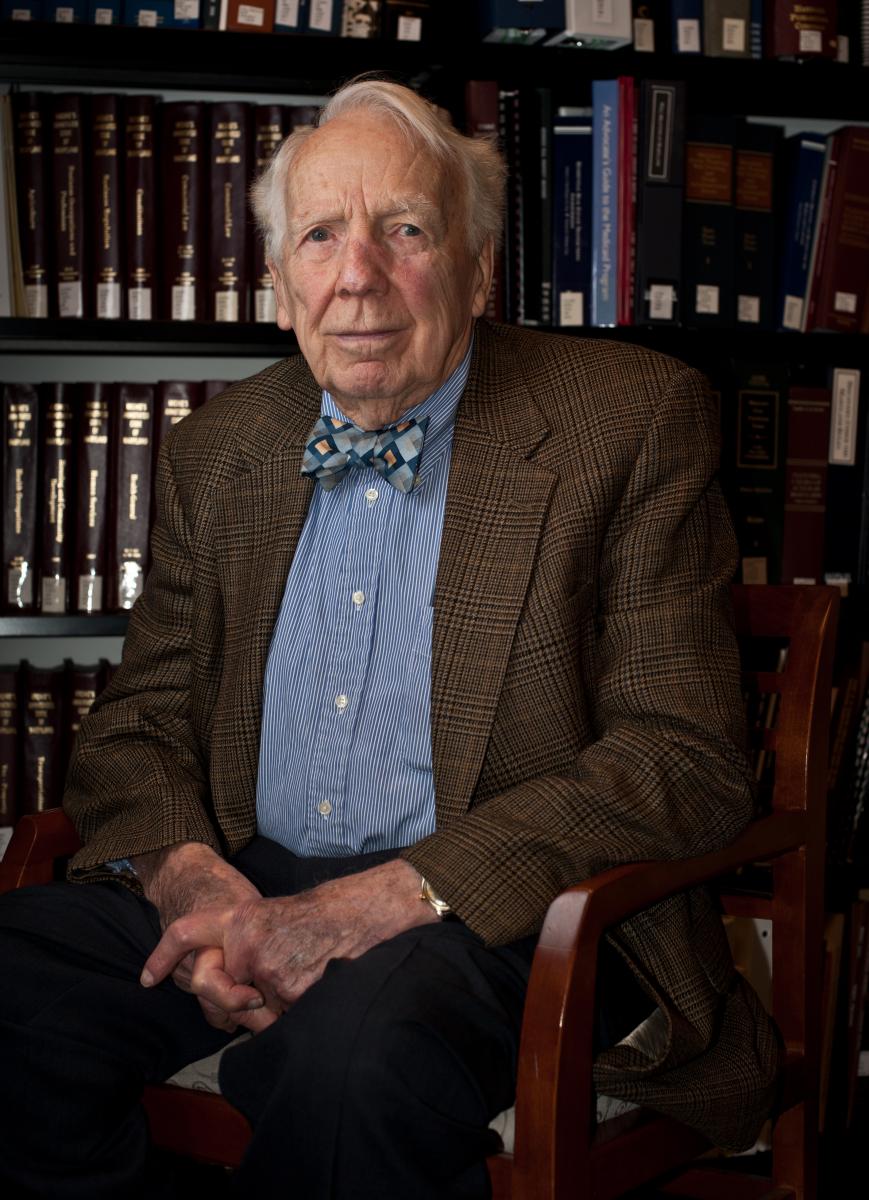

Clinton Bamberger Dies: The Loss of an Icon

By

Alan W. Houseman

Clinton Bamberger, a giant in legal aid, died last Sunday in Baltimore. He was a friend and mentor to me and many others in the civil legal aid movement. Clint’s wife of 64 years, Katharine, died in December.

Clint was the first director of the federal legal services program in the Office of Economic Opportunity in 1965 and became Executive Vice-President of the Legal Services Corporation when it first began in 1975. He was also President of NLADA.

He had an extensive career in legal education. He was Dean of the Catholic University of America's law school in the early 1970s. From 1979-1982 he worked at the Legal Services Institute in Boston with Gary Bellow and Jeanne Charn. The Institute was affiliated with Harvard and Northeastern law schools and was a unique initiative to develop a new way of training future legal aid lawyers. 1982, he joined the University of Maryland law school to build its clinical law program into a nationally distinctive effort using law students to provide free services to the poor.

Prior to his direct involvement in civil legal aid, Clint was an associate of Piper & Marbury, served as Maryland assistant attorney general from 1958 to 1959, and in 1960 became a partner at Piper & Marbury. In 1963, he argued Brady v. Maryland in the United States Supreme Court in the case that led the Court to rule that prosecutors must give defendants any evidence they possess that may indicate their innocence, known as the “Brady Rule.” Many criminal lawyers and scholars perceive the Brady Rule as one of the most significant developments in criminal justice law.

Several other accomplishments are worthy of note. In 1984, he brought a lead paint case that allowed tenants to put rent into a court-controlled account if lead-based paint was “easily accessible to a child” even without signs that the child had a high level of lead in their blood. In 1989, Clint became involved in developing a legal aid system in South Africa, prior to the end of apartheid in 1994. He was also the first board member names to the Open Society Institute – Baltimore, a foundation that seeks to address issues of poverty, criminal justice and education.

For the civil legal aid community, Clint was not just the first director of the federal program, he, along with his deputy Earl Johnson, was its architect.

He envisioned civil legal aid as a critical tool to combat poverty and emphasized the ability of lawyers to empower poor people to help themselves. Speaking to an annual meeting of the National Legal Aid and Defender Association in 1965, Clint argued that “Lawyers must be activists to leave a contribution to society. The law is more than a control; it is an instrument for social change. The role of [the] OEO program is to provide the means within the democratic process for the law and lawyers to release the bonds which imprison people in poverty, to marshal the forces of law to combat the causes and effects of poverty. Each day, I ask myself, how will lawyers representing poor people defeat the cycle of poverty?” A year later, Clint told the National Conference of Bar Presidents: “We cannot be content with the creation of systems of rendering free legal assistance to all the people who need but cannot afford a lawyer's advice. This program must contribute to the success of the War on Poverty. Our responsibility is to marshal the forces of law and the strength of lawyers to combat the causes and effect of poverty. Lawyers must uncover the legal causes of poverty, remodel the system which generates the cycle of poverty and design new social, legal and political tools and vehicles to move poor people from deprivation, depression, and despair to opportunity, hope and ambition.”

Clint and Earl fleshed out the overall design for the program. Unlike the legal aid systems that existed in other countries, which generally used private attorneys who were paid on a fee-for-service basis (known as Judicare), OEO’s plan for the legal services program in the United States utilized staff attorneys working for private, nonprofit entities. OEO’s grantees were to be full-service legal assistance providers, each serving a specific geographic area, with the obligation to ensure access to the legal system for all clients and client groups. The only specific national earmarking of funds was for services to Native Americans and migrant farmworkers.

Although OEO was able to generate proposals for federal funding from organizations eager to provide legal assistance, the legal services program also generated substantial opposition within the legal profession, mainly from local bar associations that represented private attorneys practicing in the areas that would be served by the new programs. One common response that arose out of local opposition to legal services programs was efforts by local bar associations to seek OEO funding for Judicare. However, Clint refused to fund Judicare programs as the primary model for legal services delivery, agreeing to fund only a few programs, primarily in rural areas.

In spite of the initial external controversy over Judicare, within nine months of taking office, Clint and his staff had completed the Herculean task of funding 130 OEO legal services programs. In the end, despite their initial misgivings, the OEO legal services program obtained the support of many local and state bar associations. By the end of 1966, federal funding grew to $25 million for these local programs and national infrastructure programs established to provide litigation support, training, and technical assistance. By 1968, 260 OEO programs were operating in every state except North Dakota, where the governor had vetoed the grants.

As Executive Vice-President of LSC, Clint helped shape the plan to expand to every county in the US, oversaw the development of the Office of Program Support and the Research Institute, developed some of the early delivery research which LSC undertook and provided constant guidance to the Senior Staff and President Tom Ehrlich.

At the NLADA Annual Conference in December, NLADA will hold an event celebrating the life and accomplishments of Clint. A memorial fund in Clint’s name has been established at Viva House, 26 S. Mount St., Baltimore 21223.

The New York Times: E. Clinton Bamberger, Lawyer With a ‘Fire for Justice,’ Is Dead at 90

The Baltimore Sun: E. Clinton Bamberger Jr., pioneer in legal aid for poor