Anna and I attended an event by the Marshall Project on Monday titled What’s the Story: Criminal Justice and Narrative Change. The topic of the conversation centered around one question essential to understanding the current state of our justice system: How did we get here? The panelists convened by the Marshall Project had varying fields of expertise and experience relating to policy and justice, creating a unique dialogue about change and progress. They each expressed their beliefs on the origin of our system’s inadequacies. Each panelist had an interesting point of view, and the disagreements that ensued during the panel sparked a personal reflection on how I think we have arrived at a system so convoluted and unjust.

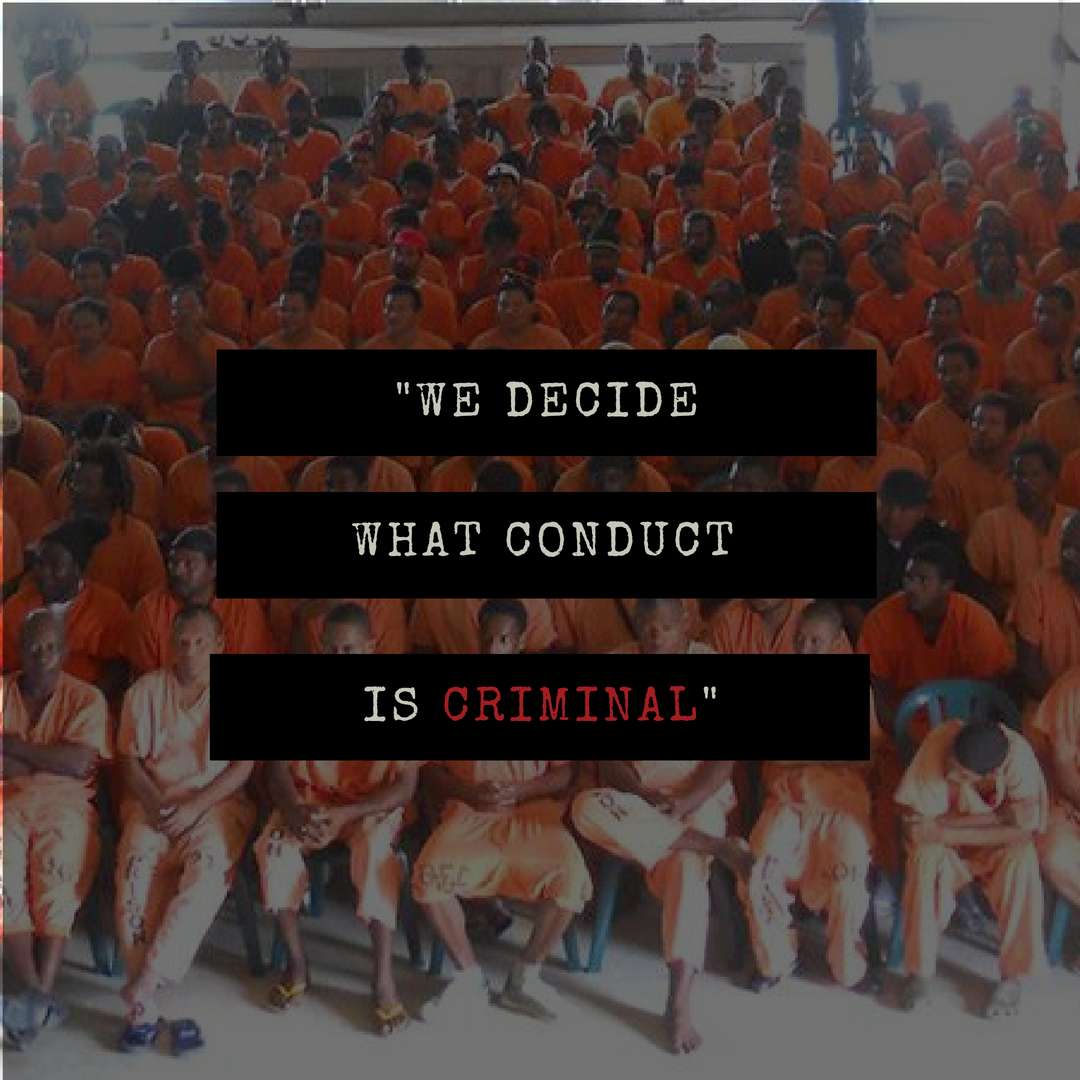

Panelist Sherrily n Ifill outlined the justice system as a construct for social control of Black and Latino populations. Coursing us through historical elements that contributed to mass incarceration, she began with the Thirteenth Amendment’s abolition of slavery and the subsequent growing concern for maintaining cheap workforce labor. In an attempt to control the growing autonomy and political power of newly freed slaves, many states implemented “black codes.” When the Thirteenth Amendment was ratified to include a provision that allowed slavery for those convicted of a crime, black codes were used to criminalize and over police the newly freed communities of African Americans and a new supply of bodies became available for slavery by another name- mass incarceration. Black codes, such as one requiring all African Americans to carry “papers” documenting their employment, allowed for rampant arrests and convictions of swaths of African Americans. These “convicts” were then funneled into various versions of labor through the convict-lease system, with many finding themselves back on plantations. With this history lesson, Ifill posited that we must face the deeply ingrained racist ideologies that have contributed to, and allowed for the perpetuation of, the disproportionate number of black and brown bodies behind bars. She asserted that only by acknowledging and understanding the role of racism as the foundation of today’s justice system can we begin to unpack our narrative on who criminals are and what justice looks like, stating, “We decide what conduct is criminal.”

n Ifill outlined the justice system as a construct for social control of Black and Latino populations. Coursing us through historical elements that contributed to mass incarceration, she began with the Thirteenth Amendment’s abolition of slavery and the subsequent growing concern for maintaining cheap workforce labor. In an attempt to control the growing autonomy and political power of newly freed slaves, many states implemented “black codes.” When the Thirteenth Amendment was ratified to include a provision that allowed slavery for those convicted of a crime, black codes were used to criminalize and over police the newly freed communities of African Americans and a new supply of bodies became available for slavery by another name- mass incarceration. Black codes, such as one requiring all African Americans to carry “papers” documenting their employment, allowed for rampant arrests and convictions of swaths of African Americans. These “convicts” were then funneled into various versions of labor through the convict-lease system, with many finding themselves back on plantations. With this history lesson, Ifill posited that we must face the deeply ingrained racist ideologies that have contributed to, and allowed for the perpetuation of, the disproportionate number of black and brown bodies behind bars. She asserted that only by acknowledging and understanding the role of racism as the foundation of today’s justice system can we begin to unpack our narrative on who criminals are and what justice looks like, stating, “We decide what conduct is criminal.”

In his narrative of improvement, Grover Norquist outlined the need to limit the government interference in people’s lives made possible through over-criminalization of various crimes which, according to him, are “vices” that then carry harsh sentences. Norquist points to liberals having “no credibility on crime,” and conservatives’ trust that the justice system had been doing its job as reasons for our current state of mass incarceration. The realization of the exorbitant costs of incarceration, according to Norquist, have driven conservatives to organize think tanks to explore, address, and give credibility to the discussion on criminal justice only once crime rates began to fall and the issue became a “safe” discussion in the political realm. “Safe” topics, campaigns, press conferences, and the importance of image are known to be central to politics. Norquist suggests these image campaigns have contributed to the proliferation of mandatory minimums and sentencing disparity we see today. Outlining his concerns with over-criminalization, he asked, “How many people know the 600,000+ things that can land you in jail?” As a solution to our mass incarceration issue, he suggested that we begin to redefine who needs to be in prison by determining whether or not we’ve incarcerated someone because “we’re mad at them” for committing a crime of vice or annoyance, or “we’re scared of them” for committing a crime with victims. Although focused on different narratives about what has led to the current state of our justice system, both Ifill and Norquist agreed that bi-partisan support is essential to creating change.

Weldon Angelos’s case became a catalyst of such bi-partisan rallying when he was sentenced to 55 years and one day for marijuana distribution. After selling weed to an undercover agent three times, he was indicted on 20 charges in his federal courts because his case was "stacked." Angelos stated that the judge presiding over his case had a reputation for being “tough on crime,” and he and his lawyer expected the worst. Contradictory to his reputation, Judge Cassell expressed disbelief for sentences he was forced to hand down on a drug-related offense. Judge Cassell reviewed the mandatory minimums for egregious crimes, and was in disbelief that, as Angelos recalled, Congress had essentially declared “rape, murder, and terrorism are all bad—but drug offending is worse." Angelos’s case outlined multiple issues in the criminal justice system like over-criminalization, mandatory minimums, and “stacking,” the practice of attaching “related” charges to a person’s original case to “punish to the full extent of the law.” According to Judge Cassell, these are problems “only Congress can fix.” Although national attention on Angelos’ case led to President George W. Bush commuting his sentence, he still lost 12 years of his life and was permanently marked by his incarceration. This experience catapulted Angelos into activism as began his work to change the “tough on crime” narrative that persists in our justice system.

In hearing this broad spectrum of opinions on justice system narratives, I wondered how we, as a community, could work to address problems that have persisted for centuries and are so deeply embedded in racism and responded to through the “tough on crime” lens. In the time since I relocated to Washington, D.C., I have had the opportunity to sit in on discussions about justice and reform and noticed that much of the discourse has focused on two recurring themes: “saving money” and “saving lives.” I found it interesting that Norquist recognized that image politics and press conferences have led to problems within the criminal justice system. Harsh crime bills and mandatory minimums that politicians propose to maintain their image are only one facet of the issue, and these policies cannot be divorced from their racial implications. According to Ifill, when we wonder how such callous laws are made we must remember what communities were intended to be subject to their consequences before we can begin to unravel the damages wrought by them.

Though we have begun the work to undo our most detrimental policies, can saving either money or lives be the sole achievement of our justice system without degrading or delaying our progress? If we are saving lives, we will have to spend money to provide services that keep people out of prison and the justice system; but if we are saving money by reducing mass-incarceration and are not addressing the underlying causes that led to arrest or conviction- those lives are still at stake. I believe that humanity should be at the forefront of the criminal justice issue, but in a country so divided on where reform should occur, I’m not sure if there is an attainable “middle ground” that does not come at the cost of human lives.

Today, progress and lives are too often sacrificed for the protection of personas and power structures. So how do we find balance when everyone is convinced by their own argument and is unwilling to concede? Is it ever okay to accept a compromise that entails the sacrifice of human lives? Is it truly commendable to shorten rather than abolish certain mandatory minimums and reduce the crack-cocaine to powder-cocaine sentencing disparity from 100:1 to 18:1 despite racialized narratives or is progress of any degree worthy of applause? Within our current societal and systematic structures, it may be unrealistic to expect giant bounds to be made in the interest of everyone. We have created systems that starve many, privilege a few and ignore or overlook the injustice they create. In the end, however, systems are based on policy and policy can always be rewritten. Once we heed the patterns of oppression that resurface with each generation and seek solutions beyond the scope ego or tradition, we can finally dismantle the obstacles that have truly kept our nation from achieving the greatness we claim.

-Kameryn